Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) was a Spanish artist who revolutionized the art world with his unique and innovative styles. No other artist’s style changed to the extent that Picasso’s did. As a result, his body of work is frequently divided into periods. What were Pablo Picasso’s principal art periods? What events caused Picasso to change his painting styles?

Picasso’s major art periods are: the Blue Period, the Rose Period, the Primitivism Period, the Cubism Period, the Neoclassicism Period, and the Surrealism Period. The paintings from each of the six periods mirror what was happening in Picasso’s life at that time.

Pablo Picasso was a prolific artist, working in various styles and movements throughout his career. Read on to learn about the timeline of the artistic periods of one of history’s greatest artists.

Picasso’s Blue Period

Table of Contents

The Blue Period began after the death of Picasso’s friend, Carlos Casagemas. In February 1901, Picasso learned that his close friend Casagemas had died while in Madrid. His long-term sadness led to his first creative breakthrough. His blue period lasted for four years until around 1904.

Picasso created a series of portraits that paid tribute to Casegamas and captured the emotions of his loss and mourning. These portraits are characterized by somber colors and distorted, almost anguished expressions, reflecting the deep sorrow Picasso felt at the loss of his dear friend. This event marked the start of Picasso’s Blue Period.

During the Blue Period, Picasso’s paintings were solemn with blue, dark, and sad colors. Hence, the name “the Blue Period.” He used shades of blue-green, green, and blues to set the mood.

Picasso sometimes painted over old works. Artists often did this because art supplies were expensive. Take Picasso’s famous Blue painting, “The Tragedy,” which he reworked from an earlier bull painting.

The Blue Period paintings depict struggling people, beggars, refugees, starving, poor, oppressed, and blind. They tend to be thin and bony, and their faces are often blank or far away. These subjects create a feeling of melancholy in his paintings.

Picasso’s Rose Period

By 1904, Picasso had switched from the blue hues and depressing themes of his Blue Period to a happier color palette, primarily red, pink, and orange. These paintings still have blue tones but differ significantly from the brighter and warmer tones.

The subjects of these paintings were usually circus people, like clowns, circus performers, and other portraits. The clown or harlequin, which Picasso drew wearing striped clothes, became a personal symbol for him. His well-known work, “The Family of Saltimbanques,” reflected this. [1]

Picasso also painted portraits of his mistresses and new lovers during this time. The best-known illustration of this is his 1905 painting “La Belle Fernande,” which features his mistress Fernande Olivier. Picasso also painted his new love, the model and artist Marie-Thérèse Walter, in “Woman with a Crow” (1906).

There was no significant event to mark the end of the blue period; instead, the artist gradually started to create happier works of art. Picasso changed his painting style because, according to some, he was content in his relationship with Fernande Olivier. At this time, Picasso settled in Montmartre, France, where he would spend time with fellow artists and poets at the Médrano circus or watch traveling entertainers on the outskirts of Paris. These people became prominent subjects, and the colors gradually became pink.

Picasso produced many portraits and floral paintings during the Rose Period. He then tried out a style that made the subjects of his portraits anonymous. The result is an art piece that looks like a person but is not a person, such as “Seated Female Nude.” [2]

Picasso’s Primitivism Period

Art from Africa and Egypt had an impact on Picasso’s Primitivism Period. This period takes its inspiration from primitive idols, statues, and masks, whose simplified shapes freed them from the movement of parts.

Due to French colonial expansion in Africa at the time, a lot of African art was transported to Paris. At the same time, that continent’s artifacts were showcased in Parisian museums. Henri Matisse, Picasso’s rival, was also interested in African figurines.

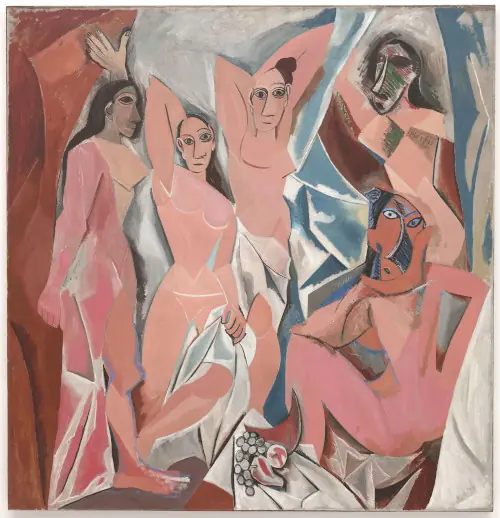

Picasso responded to Henri Matisse’s shows of Blue Nude and The Dance in 1907 and 1909 with a painting that would become known as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which helped build his reputation. He started incorporating African influences into his work with this piece. [3]

Picasso’s art started getting closer to Cubism and more abstract. Instead of creating figurative depictions of performers, he began to paint abstracted, African mask-inspired images of all kinds of people, including the artist in his piece “Self-Portrait” and prostitutes in a Barcelona brothel in “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” This led to Picasso’s Cubist Period, in which objects are broken up, analyzed, and put back together abstractly. [4]

After the release of Heart of Darkness, a novella by Joseph Conrad that critiques European colonial rule in Africa, the appalling behavior of European powers in Africa was made public. The publication of “Heart of Darkness” and the emergence of Primitivism reflected a growing interest in non-Western cultures and a critique of European imperialism.

Picasso’s Cubism Period

Picasso is best known for his cubist paintings, which show objects and subjects abstractly. Picasso’s July 1907 work was a turning point for the movement. In “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907), Picasso broke the rules of painting for the first time by depicting the female body as a series of fractured facets or color planes.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were the first artists to use single colors and shades to create Cubism. They didn’t like making art that looked like the real world. As a result, art flourished during this time. It was revolutionary in the field of painting.

Cubist paintings primarily use simple geometric objects. When Georges Braque’s paintings were on display in Paris in 1908, critic Louis Vauxcelles remarked that they reduced everything to “geometric outlines, to cubes,” where the term “cubism” appears to have come from. [5]

After about ten years, Picasso started putting natural objects into his paintings as collages. Picasso’s first collage, “Still Life with Chair Caning,” from 1912, featured an oilcloth piece with a chair-caning pattern printed on it that was adhered to the canvas. During the 1910s and 1920s, Picasso continued to make collages. He made a lot of pieces that used different things, like newspaper clippings, fabric, and found objects.

Picasso’s Neoclassicism Period

After World War I, it became common for artists to paint in a style that looked like it was from long ago. Picasso joined in on this trend, giving birth to the following Neoclassicist paintings: [6]

- Two Nudes (1906)

- Large Bather (1921)

- Two Women Running on the Beach (1922)

The Neoclassicism Period was inspired by Picasso’s first trip to Italy, where we saw the naturalism of the Italian Renaissance. He went to the Vatican and the Naples archaeological museum to see their famous collections of ancient sculptures. He also visited Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Naples museum to see many Roman paintings and mosaics.

Some Renaissance artists had an influence on Picasso’s works during this period. On his trip, he saw a lot of Renaissance artwork in Florence and Rome, including works by Raphael, Michelangelo, and the Primitives.

Picasso’s Surrealism Period

The surrealist art movement became popular, so Picasso was in the same group as other surrealist artists. Together with Picasso, René Magritte, Joan Miro, and Salvador Dali are the most well-known Surrealist painters.

Picasso did not fully subscribe to Surrealism’s ideals, although his artwork from this period featured distorted figures and fragmented forms in the surrealists’ signature style. He thought it was wrong that they didn’t want to use technology, which he thought was good for society.

Surrealists spoke out against the rationalism and technological progress that led to the horrors of World War 1. Instead, they trusted in the parallel universes of chance, desire, coincidence, and dreams. To make art as “beautiful as the accidental meeting, on an operating table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella” was the aim. [7]

During this period, Picasso was also influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud and even adopted some ideas about the unconscious mind in his art. For instance, he used unconventional techniques such as automatic drawing, allowing the hand to move freely without conscious control. By doing this, he could access his subconscious and create art that broke free from conventional artistic norms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Picasso and Braque founded Cubism in the early 1900s. Cubist art fragments and reassembles objects and forms to create a geometric, abstract reality. Cubism represented multiple viewpoints and created depth and movement on a two-dimensional canvas. On the other hand, Surrealism explored the subconscious and the irrational in the 1920s. Salvador Dali, René Magritte, and Max Ernst used surrealist imagery to express their feelings.

Cubism is divided into two distinct phases: Analytic Cubism and Synthetic Cubism.

Analytic Cubism (1907-1912) is a style of painting where objects and forms are fragmented and reassembled, creating a geometric and abstract representation of reality. On the other hand, Synthetic Cubism (1912-1914) replaced Analytic Cubism’s monochromatic palette with bright colors and varied materials.

Picasso and Braque founded Cubism in the early 1900s. Cubist art fragments and reassembles objects and forms to create a geometric, abstract reality. Cubism represented multiple viewpoints and created depth and movement on a two-dimensional canvas. On the other hand, Surrealism explored the subconscious and the irrational in the 1920s. Salvador Dali, René Magritte, and Max Ernst used surrealist imagery to express their feelings.

References

- Blum, Harold P., and Elsa J. Blum. “The Models of Picasso’s Rose Period: The Family of Saltimbanques.” The American Journal of Psychoanalysis 67.2 (2007): 181-196., https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/palgrave.ajp.3350023.

- Millard, Charles W. “Picasso Brujo.” The Hudson Review 34.1 (1981): 77-92., https://www.jstor.org/stable/3851081.

- Cordova, Ruben Charles. “Primitivism and Picasso’s early Cubism.” University of California, Berkeley, 1998., https://www.proquest.com/openview/0558633a0fa3e750febc0c3f36018325/1.

- Golding, John. “The’Demoiselles d’Avignon’” The Burlington Magazine 100.662 (1958): 155-163., https://www.jstor.org/stable/872425.

- Ganteführer-Trier, Anne. Cubism. Taschen, 2004., https://books.google.com/books?id=TEM5BoZQjl0C.

- Howard, Seymour. “Picasso’s neoclassic outlines: An archaeology of consciousness.” International Journal of the Classical Tradition 2 (1996): 560-566., https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02677891.

- Swami, Viren, et al. “Beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella! Individual differences and preference for surrealist literature.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 6.1 (2012): 35., https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024750.