When people talk about art, Picasso is undoubtedly one of the most frequently discussed artists. Even non-artistic people have heard of him and his works. So what is his technique that has everyone so excited?

Picasso’s technique used imagination to create abstract works that explored form and structure. Picasso used colors and brush strokes to give texture to his figures which he broke down into geometric shapes. He built paintings in layers and used color to fragment the shapes of objects.

His technique is famous around the world because of its uniqueness. Eventually, it made a massive difference in the art we know now. Picasso’s works are one of the most sought-after subjects in many forums, art galleries, or exhibits. His works are world-class! They are even recognizable by pigeons. [7]

| Name | Pablo Ruiz Picasso |

| Date of Birth | 25 October, 1881 |

| Date of Death | 8 April, 1973 |

| Location | Spain |

| Movements | Cubism, Surrealism |

| Artistic Focus | Paintings, Drawings, Sculpture |

| Favorite Medium | Oil on Canvas |

His famous technique causes the subjects of Picasso’s paintings to have unique and weird faces that give character to his distinct and recognizable style. It was important to highlight how he achieved this style, but it is equally important to discuss why he painted this way.

Why Did Picasso Paint So Weirdly?

Table of Contents

Picasso’s style is abstract and eye-catching. Many factors influenced Picasso’s forms and artistic vision. Covering these factors is crucial to understanding Picasso.

As a general rule, Picasso’s ‘weird’ and abstract style originates from painting his thoughts rather than painting what he sees. Picasso drew inspiration from the Basque people and their suffering during bombings when he painted Guernica. For this reason, he distorted faces in his paintings.

Picasso disregarded the realism of his subject and used creative forms and colors to convey emotions and thoughts.

At a young age, Picasso showed prominent talent but he had also seen and experienced unfortunate events – including the death of his sister.

Trauma over his life helped influence his works, and some appear either sad, ugly, or distorted.

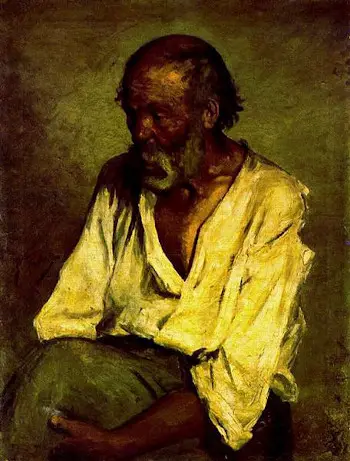

At only fourteen, he had already painted the Old Fisherman. It is a lesser-known painting that is not in many history books.

This early painting is realistic and doesn’t follow the distinctive and distorted style of Picasso’s later works.

One period of Picasso’s life is known as the ‘blue period’ and started after the suicide of one of his friends. The paintings like Old Guitarist contain blues and darker tones and often depict Picasso’s friend in different scenes. [4]

We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies. If he only shows in his work that he has searched, and re-searched, for the way to put over lies, he would never accomplish anything.

Pablo Picasso [1]

Most of his works span different phases in his life. In these phases, he put all of his thoughts, emotion, time, and dedication into his art. For these complex masterpieces, it is natural to wonder how he starts them, what his preparations are, and how long it takes him to finish!

How Long Did It Take Picasso to Complete a Painting?

For most masterworks of art, the artist spends years working on the painting. Among all of the artists I investigated for the Style Guide series, Picasso was one of the fastest painters. How fast is fast?

On average, Picasso painted ~1.95 paintings per day. Over his 70 years of painting, Picasso painted over 50,000. He was known as a fast painter and used broad strokes and abstract outlines of shapes and forms. On some days avoiding distraction, he would produce 3 paintings.

Usually, he would start his day at 11 am and work on his paintings at an average of 13 hours a day. His dedication and passion for his craft are why he poured hours every day into his paintings. He would work on two subjects and finish them within the day. Whenever he had long sessions, he always made sure that there were no distractions or interruptions.

It isn’t up to the painter to define the symbols. Otherwise it would be better if he wrote them out in so many words! The public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them.

Pablo Picasso [2]

Amazingly, such a heavy routine did not cause Picasso to burn out from exhaustion. One reason is that he constantly searched and explored for inspiration.

He loved painting so much that he didn’t mind spending thirteen hours a day looking at his canvas and holding his brush. He let his surroundings and the people around him influence and inspire.

Seventy years is a long time to spend painting, and over this time Picasso changed and grew as a person.

As you would expect, his artwork grew and evolved along with him. Many notice the stark differences between his early works and his later wonders. [5]

Why Did Picasso’s Style Change So Much?

Looking at some of Picasso’s early paintings might surprise some – I only knew his abstract work and was interested in the realistic paintings from the blue and rose periods of his life. In the rose period, Picasso fell in love and made brighter paintings in a French style, with many classical influences. [8] Afterward, there was a large change to his painting.

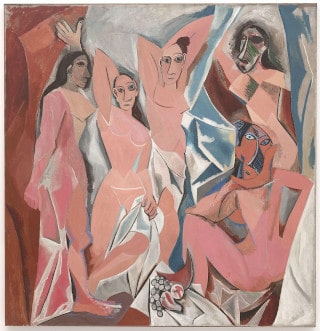

As a whole, Picasso’s style changed because he invented Cubism and moved towards creating abstract paintings instead of realistic ones. Cubism paints objects from multiple viewpoints and breaks the figure down into abstract geometric shapes which are often reassembled or shuffled.

Some mistakenly believe that his style changed because of the Spanish Civil War, but this view is not explained by the timeline. Picasso invented Cubism in 1907-1908, but the civil war was not until 1936. Like many artists, the tragedy and horrors of the war certainly affected Picasso’s work. However, his distinctive abstract style was created much earlier.

| # | PAINTING NAME | YEAR PAINTED | LOCATION |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guernica | 1937 | Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain |

| 2 | Les Demoiselles D’Avignon | 1907 | Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| 3 | The Weeping Woman | 1937 | Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom |

| 4 | The Old Guitarist | 1903-1904 | Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, United States |

| 5 | Le Reve | 1932 | Private Collection, United States |

| 6 | Three Musicians | 1921 | Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| 7 | Girl Before a Mirror | 1932 | Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| 8 | La Vie | 1903 | Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, United States |

| 9 | Ma Jolie | 1911-1912 | Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| 10 | Family of Saltimbanques | 1905 | National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, United States |

Picasso had an undying thirst for innovation and originality. He was constantly seeking new ideas and wanted to improve his style. Before he shifted from realism to cubism, Picasso’s style was similar to everyone else’s technique. He would study different lessons about art and practice them. He wanted to push the boundaries of art, so he started progressing from his current realistic style into a more abstract technique – cubism.

In one instance, Picasso overheard a critic referring to a painting’s background as ‘negative space.’ This incident helped inspire Picasso to create Cubism. Cubist works have interesting backgrounds, but the style created confusion in the minds of viewers of the time.

Artists were often misunderstood or critiqued because of their particular way of painting. Often, messages behind the style of each piece were missed or misinterpreted. To critics of the day, it depicted chaos and disorder.

The civil war would have an influence on his work later in life. The experiences of chaos, sorrow, and despair are reflected in the painting from life in Spain during the fascist period. It was a dark and painful time for many in the country. As mentioned previously, Guernica resulted from these influences. The distorted faces in the painting hint at the suffering of war.

Over time, Cubism itself grew more popular and began to change. More artists joined the movement and their creations influenced and played off each other. The early Cubism of Picasso and Braque gave way to different styles.

The Difference Between Analytical and Synthetic Cubism

The term Analytical Cubism was invented by Cubist painter Juan Gris. He used it to differentiate the earlier works from what came later. Mostly, the terms are used by historians and were not used by the artists of the time. Let’s break down the differences.

As a whole, the difference between Analytical and Synthetic Cubism originates from the materials used to produce the art. Analytical cubism started first and only uses paint to produce the style. Synthetic cubism also uses a collage of newspapers and magazines to produce pattern and texture.

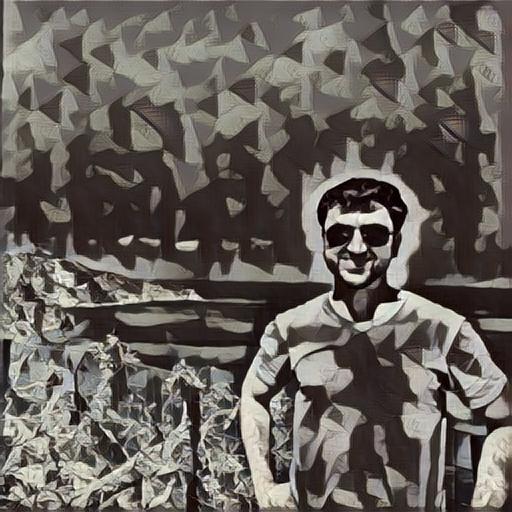

Analytic Cubism is the phase in the cubism movement popularized by Picasso and Braque.

It focuses on natural objects in light of discernible features that, with time, become symbols or clues that reveal the object’s concept.

This type of cubism studied the use of primitive shapes and overlapping surfaces to express the unique forms of the subjects in a painting.

Analytical Cubism had nearly purely flat art and emphasized descriptive shape rather than obtrusive details using several dimensions and a muted color palette.

Analytical cubism broke centuries-old painting principles by delivering a substitute to a single point linear perspective.

Abstract art is only painting. And what’s so dramatic about that? There is no abstract art. One must always begin with something. Afterwards one can remove all semblance of reality; there is no longer any danger as the idea of the object has left an indelible imprint. It is the object which aroused the artist, stimulated his ideas and set of his emotions. These ideas and emotions will be imprisoned in his work for good.

Pablo Picasso [3]

Artworks during this period became hard to distinguish or understand. There was sometimes no way of knowing what the subjects were. Picasso and Braque played with space distortion. Analytic Cubism was taken to its logical conclusion by the pair. Colors became more monochromatic, planes were more complexly layered, and compressed space even more than before. [9] An excellent example of this cubism is Picasso’s Ma Jolie, painted from 1911 to 1912.

Synthetic Cubism grew out of analytical cubism. Synthetic Cubism had a more lively color. This shift in the color palette is one of the significant differences between the two forms of cubism. One of the main characteristics of Synthetic Cubism is the integration of collage. The technique uses other materials to produce painting styles and designs. Often, these materials added pattern and texture to the art. Synthetic Cubism literally blended real-world objects onto the canvas, bridging realism and art. [6]

Often, Picasso adopted collage when two or more overlaying planes shared the same hue. He used actual pieces of paper instead of painting flat depictions of paper, and actual music scores supplemented written musical notation. However, as Synthetic Cubism started forming its norms, it rocked the European art scene. Synthetic Cubism was about leveling out the scene and wiping away the last remnants of allusion to three-dimensional space.

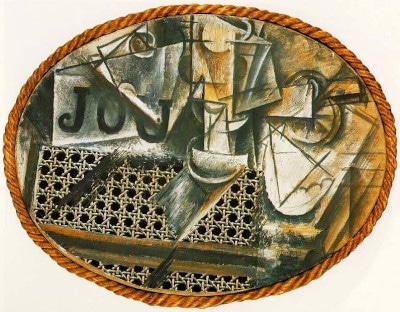

Picasso’s Still Life With Chair Caning was his very first collage piece. The artwork incorporated a long rope, an oilcloth, and other materials commonly available at the artist’s disposal. The oilcloth motif resembled the chair’s bars, while the rope served as a picture frame. The most groundbreaking component of the compositions was placing a piece of a chair on the work instead of an actual chair.

Looking for inspiration from other styles for your own artwork and style transfers?

- Express your creative side by checking out the Van Gogh Style Guide

- Get an impression of Monet’s masterpieces in the Monet Style Guide

- Go on an abstract adventure with the Jackson Pollock Style Guide

- Take a Rothko Retrospective with the Mark Rothko Style Guide

- Journey through the symbolic depths with Frida Kahlo’s Style Guide

- Discover Dali’s surreal style with the Salvador Dali Style Guide

Want to learn more about how style transfers and neural networks work?

- Don’t lose out on my article about what content loss is!

- Want to know about Dropout in your own networks? Check out my post on if you should always use Dropout.

- Want to learn more about the influential VGG network? Check out my post covering why VGG is so common!

- Improve your training data using Data Augmentation techniques!

Cubism Concluded

Pablo Picasso is among the most prominent artists throughout the world. His works made a huge contribution to the evolution of art throughout time. His style originally became criticized as weird, tragic, or unfortunate. Throughout his entire life, he crafted many masterpieces and, his genius has influenced many aspiring artists.

Interested in a basic overview of style transfers? Read my post about Style Transfers, Neural Networks, and Digital Art.

The best way to do style transfers is using neural networks. If you want to learn more about one of the network types, check out my tutorial about implementing Bayesian Neural Networks using the most popular python libraries.

If you want to check out other styles, see some of the Style Guides in the Style Transfers category.

Get Notified When We Publish Similar Articles

References

- De Zayas, Marius. Picasso Speaks. The Arts, vol 3. New York, 1923. Page 315.

- Rowlandson, William. Reading Lezama’s Paradiso. Vol. 3. Peter Lang, 2007. Page 115.

- Ottinger, Didier, ed. Futurism. 5Continents, 2009.

- Casadio, Francesca, et al. “Scientific investigation of an important corpus of picasso paintings in antibes: new insights into technique, condition, and chronological sequence.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 52.3 (2013): 184-204. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/1945233013Y.0000000013

- Fitz, Linda T. “Gertrude Stein and Picasso: The language of surfaces.” American Literature 45.2 (1973): 228-237. http://alagrayson.oucreate.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/SteinandPicasso.pdf

- Krauss, Rosalind. “In the name of Picasso.” October 16 (1981): 5-22. https://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art192b/krauss%20-%20in%20the%20name%20of%20picasso%20(1).pdf

- Watanabe, Shigeru, Junko Sakamoto, and Masumi Wakita. “PIGEONS’DISCRIMINATION OF PAINTINGS BY MONET AND PICASSO.” Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior 63.2 (1995): 165-174. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1334394/pdf/jeabehav00221-0041.pdf

- Mallen, Enrique. “Pablo Picasso and the Truth of Greek Art.” Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts 1 (2014): 283-298. https://www.atiner.gr/journals/humanities/2014-1-4-1-Mallen.pdf

- Farrell-Beck, Jane A., and Jan VerPloeg Petsch. “Colors compared: Matisse and Picasso with Chanel and Vionnet.” Home Economics Research Journal 13.2 (1984): 206-214. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1077727X8401300212